5th of Jan 2019: a lot has been happening since I initially wrote this post. Azure DevOps released a free tier for open source projects, the Cake and GitVersion contributors have been hard at work to take advantage of the latest features of .NET Core. So much things have changed that I decided to update this post to reflect the current state of affairs (inclusion of Azure DevOps, upgrade to .NET Core 2.2, utilisation of .NET Core global tools and removing the Mono requirement on Unix platforms).

As a developer I’m amazed by the number of free tools and services available. I wanted to create an end-to-end demo of a CI/CD pipeline that would include:

- Trigger a build on commit

- Use semantic versioning

- Run tests

- Publish test results

- Create NuGet packages

- Publish the NuGet packages

- Create a GitHub release

For my purpose I wanted anonymous users to have access to a read-only view. I initially selected AppVeyor as it seems to be the most popular choice for .NET open-source projects. But while browsing around I discovered than projects were often using more than one platform. Travis CI and CircleCI seemed to be the two other prevailing options. Since the initial version of this post, Azure DevOps has released a free and unlimited plan for open source projects. I decided to leverage the four platforms so that I could highlight their pros and cons.

Configuration

The code is hosted on the GitHub repository Cake build. It’s named Cake after my favourite build automation system and the project is using Cake as its build system.

AppVeyor, Azure DevOps, CircleCI and Travis CI all use YAML configuration files. This means that your build steps are living in the same space than your code and this presents several benefits:

- Any developer can modify the build

- The project is self-contained

- Developers don’t have to search where the build is located

- It doesn’t matter if something terrible happens to the build server

- Ability to run the build locally on some platforms

I’m sure you’ll be as surprised as I was when I realised how simple the YAML files are:

AppVeyor: appveyor.ymlAzure DevOps: azure-pipelines.ymlCircleCI: .circleci/config.ymlTravis CI: .travis.yml

The code

The project is useless. What is important is that it describes a real-life scenario:

- The solution contains two projects which will be packed as

NuGetpackages- The

Logicproject references aNuGetpackage from nuget.org via aPackageReference,dotnet packwill turn this into a package reference. - The

SuperLogicproject depends onLogicand when packing, this project reference will be turned into aNuGetpackage reference (handled out of the box bydotnet pack)

- The

- The projects target both

nestandard2.0andnet461so they can also be used with the.NET Framework(net461and above)- The resulting

NuGetpackages should containDLLs for both frameworks

- The resulting

- The projects reference a third project that should be embedded as a

DLLrather than being referenced as aNuGetpackage- This is not yet supported by the new tooling but can be achieved.

Cake

Mono

Mono is not required any more when building on Linux and macOS. This is a massive achievement from the Cake and GitVersion contributors. The build step installing Mono on CircleCI and Travis CI never took less than 5 minutes and would sometimes take over 10 minutes on Travis CI! As a result the build script has been simplified and is doing less platform specific handling.

Pinning Cake version

Pinning the version of Cake guarantees you’ll be using the same version of Cake on your machine and on the build servers. This is enforced via the bootstrap scripts for developers’ machines (bootstrap.ps1 on Windows, bootstrap.sh on Unix) and in the YAML files for the build servers.

Semantic versioning

As I’m releasing packages I decided to use semantic versioning.

Consider a version format of

X.Y.Z(Major.Minor.Patch). Bug fixes not affecting the API increment the patch version, backwards compatible API additions/changes increment the minor version, and backwards incompatible API changes increment the major version.

Semantic versioning allows the consumers of your binaries to assess the effort to upgrade to a newer version. Semantic versioning should not be used blindly for all kinds of projects. It makes a lot of sense for a NuGet package but it doesn’t for a product or an API for example.

Versioning in .NET

In .NET we use four properties to handle versioning:

AssemblyVersion,AssemblyFileVersionandAssemblyInformationalVersionto version assembliesPackageVersionto version aNuGetpackage

Versioning an assembly

These two StackOverflow are great at explaining how to version an assembly.

AssemblyVersion: the only version theCLRcares about (if you use strong named assemblies)

Curiously enough the official documentation is sparse on the topic but this what I came up with after doing some reading:

AssemblyVersioncan be defined as<major-version>.<minor-version>.<build-number>.<revision>where each of the four segment is a16-bitunsigned number.

AssemblyInformationalVersion:stringthat attaches additional version information to an assembly for informational purposes only. Corresponds to the product’s marketing literature, packaging, or product name

AssemblyInformationalVersion is well documented.

AssemblyFileVersion: intended to uniquely identify a build of the individual assembly

Developers tend to auto-increment this on each build. I prefer it linked to a commit / tag to be able to reproduce a build. I also use the same string for AssemblyInformationalVersion and AssemblyFileVersion (I’m a bad person I know).

Versioning a NuGet package

PackageVersion: A specific package is always referred to using its package identifier and an exact version number

NuGet package versioning is described here.

GitVersion

I’ve implemented semantic versioning using GitVersion. I recommend using GitHub Flow when working on a simple package. In my experience Trunk Based Development tends to lead to lower code quality. Developers push early and often thinking they will fix it later but we all know than in software development later means never.

GitVersion produces an output that will allow you to handle even the trickiest situations:

{

"Major":0,

"Minor":2,

"Patch":3,

"PreReleaseTag":"region-endpoint.2",

"PreReleaseTagWithDash":"-region-endpoint.2",

"PreReleaseLabel":"region-endpoint",

"PreReleaseNumber":2,

"BuildMetaData":"",

"BuildMetaDataPadded":"",

"FullBuildMetaData":"Branch.features/region-endpoint.Sha.1f05a4bb4ebda8b293fbd139063ce3af22b1935a",

"MajorMinorPatch":"0.2.3",

"SemVer":"0.2.3-region-endpoint.2",

"LegacySemVer":"0.2.3-region-endpoint2",

"LegacySemVerPadded":"0.2.3-region-endpoint0002",

"AssemblySemVer":"0.2.3.0",

"FullSemVer":"0.2.3-region-endpoint.2",

"InformationalVersion":"0.2.3-region-endpoint.2+Branch.features/region-endpoint.Sha.1f05a4bb4ebda8b293fbd139063ce3af22b1935a",

"BranchName":"features/region-endpoint",

"Sha":"1f05a4bb4ebda8b293fbd139063ce3af22b1935a",

"NuGetVersionV2":"0.2.3-region-endpoint0002",

"NuGetVersion":"0.2.3-region-endpoint0002",

"CommitsSinceVersionSource":2,

"CommitsSinceVersionSourcePadded":"0002",

"CommitDate":"2018-01-31"

}In my case I’m using:

AssemblySemVeras theAssemblyVersionNuGetVersionas theAssemblyInformationalVersion,AssemblyFileVersionandPackageVersion

If you want to handle rebasing and Pull Requests you’ll have to use a more complex versioning strategy (keep in mind that GitHub does not support rebasing in Pull Requests).

As an aside Cake allows you to set the AppVeyor build number.

Run the tests

As Travis CI and CircleCI are running on Linux and macOS they don’t support testing against net461. Luckily the framework can be enforced using an argument: -framework netcoreapp2.0.

Publish the test results

CircleCI

CircleCI has a few quirks when it comes to testing.

First it only support the JUnit format so I had to write a transform to be able to publish the test results. Then you must place your test results within a folder named after the test framework you are using if you want CircleCI to identify your test framework.

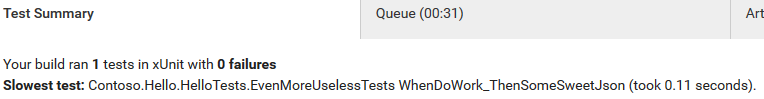

When the tests run successfully CirceCI will only display the slowest test:

I don’t understand the use case, I would prefer the list of tests and timing and the ability to sort them client-side.

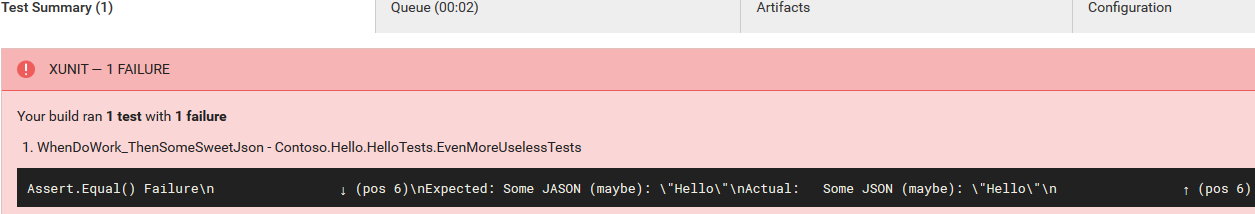

The output for failed tests is not ideal but it might be due to the way I transform the test results:

I decided not to invest more time on this as CircleCI has zero documentation around publishing test results.

AppVeyor

Again, the integration between Cake and AppVeyor shines in this area as Cake will automatically publish the test results for you (I wondered why I had duplicate test results until I RTFM).

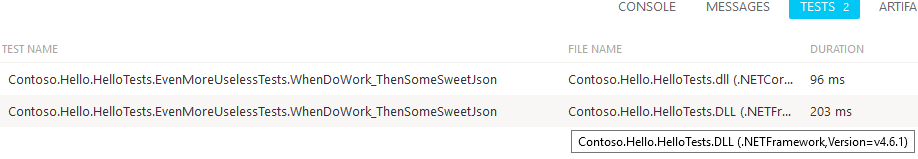

AppVeyor displays all the tests but you must hover to see the framework used:

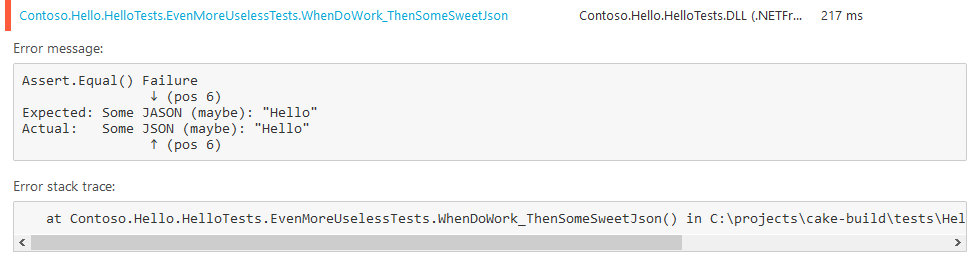

Failed tests come with a nice formatting and a StackTrace:

Travis CI

What about Travis CI you may ask. It turns out Travis CI doesn’t parse test results! All you can rely on is the build log, luckily for us xUnit is awesome:

Contoso.Hello.HelloTests.EvenMoreUselessTests.WhenDoWork_ThenSomeSweetJson [FAIL]

Assert.Equal() Failure

↓ (pos 6)

Expected: Some JASON (maybe): "Hello"

Actual: Some JSON (maybe): "Hello"

↑ (pos 6)Create NuGet packages

.NET Core is leveraging the new *.csproj system and this means:

- No more

packages.config - No more

*.nuspec - No more tears

The references (projects and packages) and the package configuration are both contained in the *.csproj making it the single source of truth!

Referencing a project without turning it into a package reference

Sometimes you want to include a DLL in a NuGet package rather than add it as a package reference.

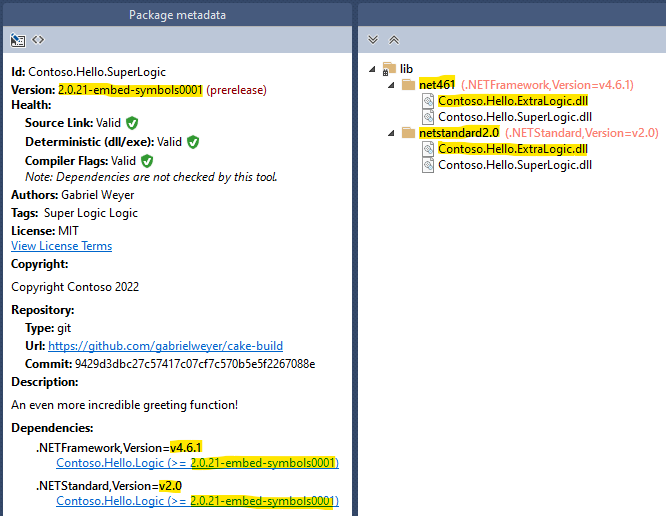

The SuperLogic project depends on the ExtraLogic project but we don’t want to ship ExtraLogic as a package. Instead we want to include Contoso.Hello.ExtraLogic.dll in the SuperLogic package directly. Currently this is not supported out of the box but the team is tracking it.

Luckily this issue provides a workaround. All the modifications will take place in SuperLogic.csproj.

- In the

<PropertyGroup>section add the following line:

<TargetsForTfmSpecificBuildOutput>$(TargetsForTfmSpecificBuildOutput);IncludeReferencedProjectInPackage</TargetsForTfmSpecificBuildOutput>- Prevent the project to be added as a package reference by making all assets private.

<ProjectReference Include="..\ExtraLogic\ExtraLogic.csproj">

<PrivateAssets>all</PrivateAssets>

</ProjectReference>- Finally add the target responsible of copying the

DLL:

<Target Name="IncludeReferencedProjectInPackage">

<ItemGroup>

<BuildOutputInPackage Include="$(OutputPath)Contoso.Hello.ExtraLogic.dll" />

</ItemGroup>

</Target>The result is the following NuGet package:

And the assemblies have been versioned as expected:

[assembly: AssemblyFileVersion("1.0.5-fix-typos0003")]

[assembly: AssemblyInformationalVersion("1.0.5-fix-typos0003")]

[assembly: AssemblyVersion("1.0.5.0")]Note: you can also use the new *.csproj system for .NET Framework NuGet packages. You don’t need to target .NET Core to take advantage of it.

Publish the NuGet packages

On any branches starting with features/, the NuGet packages will be published to a pre-release feed. If the branch is master it’ll be published to the production feed. This is handled by AppVeyor in this section of the configuration.

As this is a demo project both feeds are hosted by MyGet. For my other projects I use MyGet to host my pre-release feed and NuGet for my production feed.

When publishing the packages, I’m also publishing the associated symbols to allow consumers to debug through my packages.

Strangely enough Travis CI does not support artifacts out of the box. You must provide an S3 account if you wish to save your build artifacts.

Create a GitHub release

AppVeyor also creates GitHub releases.

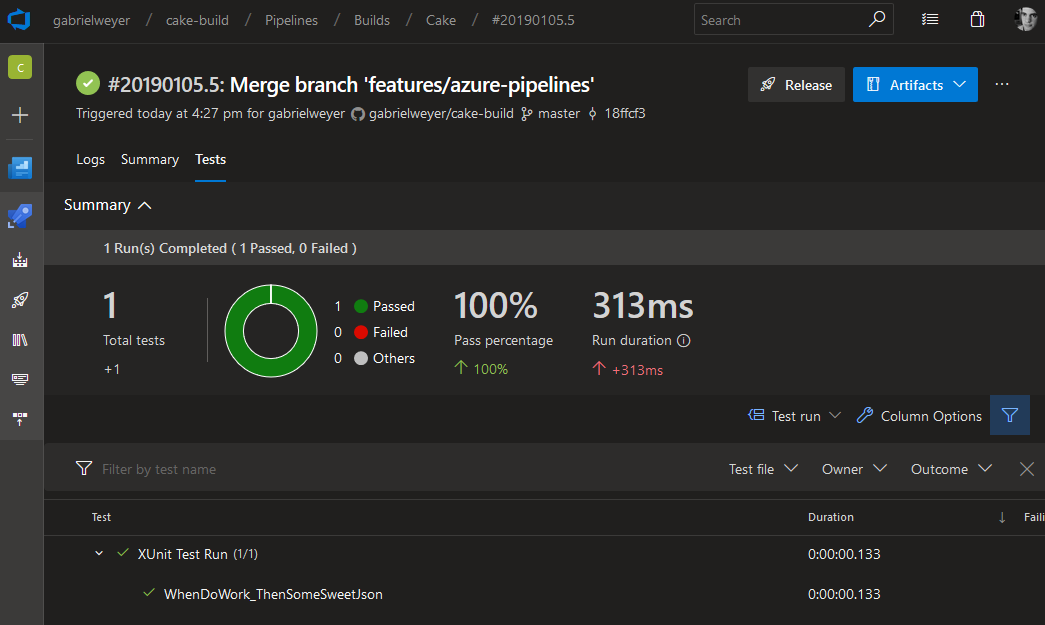

What about Azure DevOps

Azure DevOps is the only product that supports Windows, Linux and macOS. Microsoft has been iterating relentlessly and the GitHub acquisition will likely lead to a tighter integration between the two services.

Azure DevOps has the most powerful tests results tab:

One thing I’ve noticed is that builds seem to be slower on the Hosted Ubuntu 1604 agents than on the Hosted VS2017 agents.

Conclusion

This is one possible workflow only. I’ve glossed over many details and taken some shortcuts (for example there is no support for PR builds).

Those are the key takeaways:

- Do upfront planning on how you want to handle versioning. This is the hardest part and the one that will be the hardest to fix later on. Read the GitVersion documentation carefully before making any decision.

- Do what works for your team. If you didn’t have any issues with auto-incrementing your builds, keep doing so. There is no point bringing additional complexity to fix a problem you don’t have.

- Don’t assume you’ll be running on

WindowswithVisual Studio Enterpriseinstalled. Adding cross-platform or otherIDE(Rider,Code…) support from the start will make your life easier down the track.